Laura Clark

“The Illusion of Permanence”

About the Show

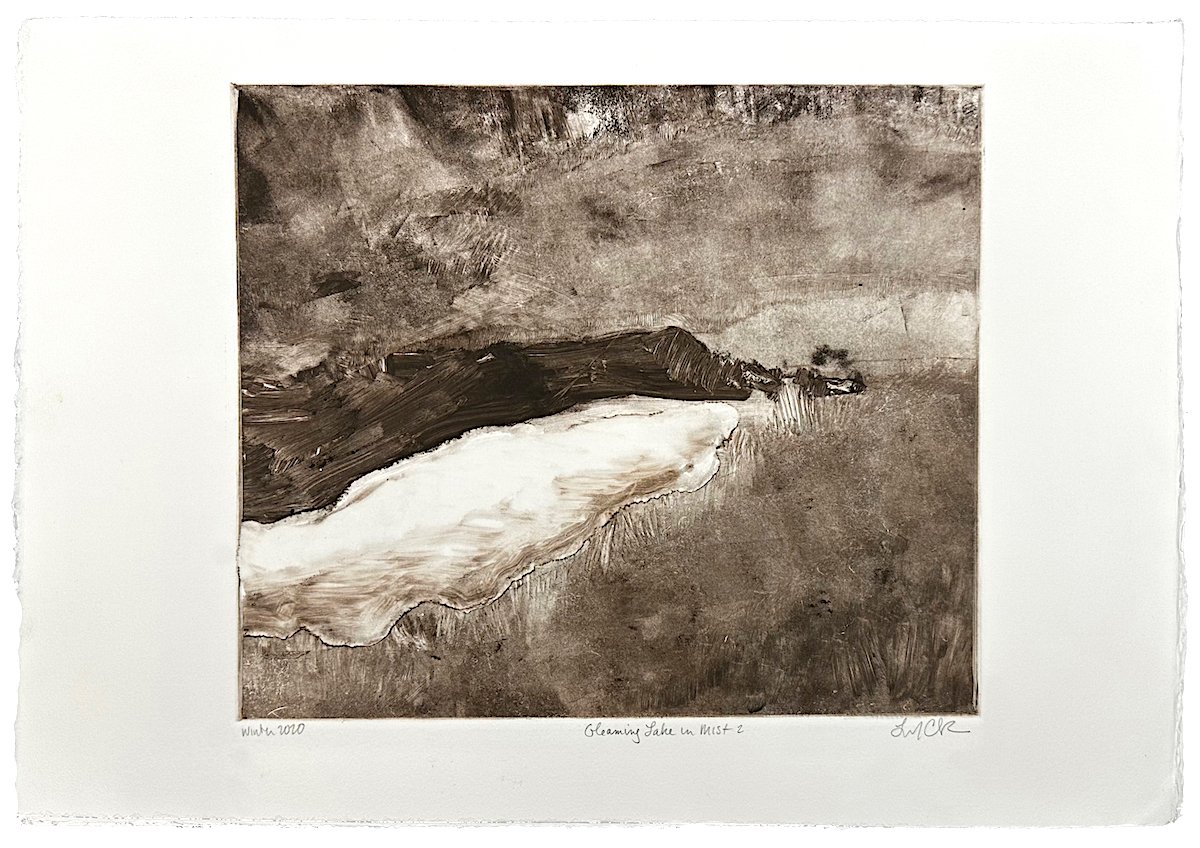

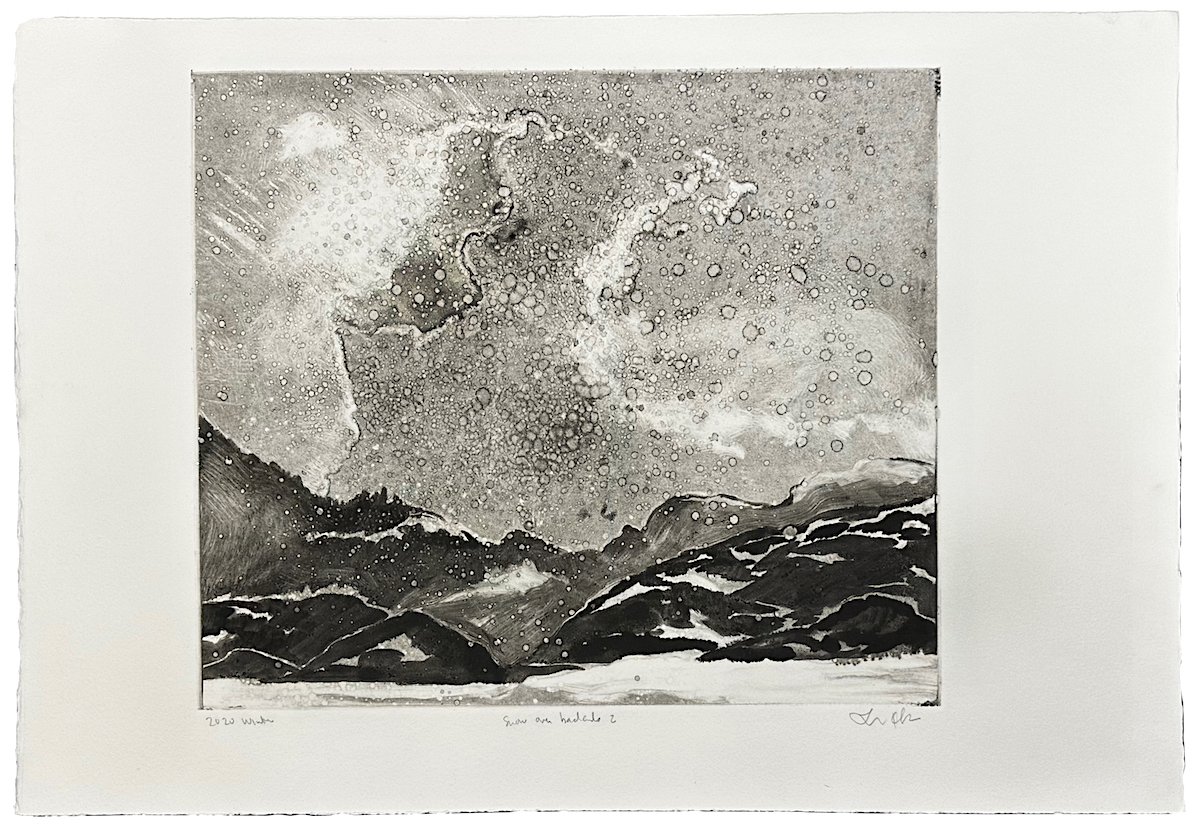

The Illusion of Permanence is an exploration of aspects of images from Ansel Adams’ work in the national parks. When Adams took his photographs, global warming was not something that anyone was thinking about, though he was certainly aware of the need to preserve wild lands in the face of expanding industrialization and its privatizing for ranches and farming. He would have been horrified to think that we could destroy the climate and atmosphere, and the concept of the planet becoming uninhabitable for most of what we recognize as “nature” would have been inconceivable. His photographs evoke a feeling of permanence, as if the mountains, trees and water he depicts will never change; even the light in his images has a fixed quality, excruciatingly beautiful, and frozen in time. In the context of what we now call ‘global warming’ this aspect of his work seems strange, almost supernatural. As our government chips away at even land reserved “eternally for posterity,” more than ever it is important to recognize the things that exist in protected parks and few remaining truly wild places we all enjoy. This show reflects my visual relationship with Adams, and my thoughts about the land his work champions.

Recently, it is in the polar regions that we see the most devastation. I am in debt to, of all things, the Amazon Prime series Fortitude (which takes fortitude to watch, I must add) for its stark images of the ice of the far north and dark message about what happens when prehistorically frozen entities begin to thaw. I watched it obsessively for days, freezing the frame to sketch the cracks and fissures in ice, and the blacks and whites of the relentless, white, frozen landscape it depicts. The show is violent and disturbing, and I was forced to watch it to get to the images that fascinated me. Soon I found myself troubled at night by dark dreams which dealt with destruction, linked with the terror I feel at the natural disaster we are already experiencing as more and more species become extinct.

So far, mountains, trees and lakes persist. The clouds are still in the sky, and nature is still spectacular, though often so much a part of us we do not notice it. We will when it is gone. These prints are my attempt to make permanent some of what I no longer take for granted. Their monochromatic nature, though, puts them in the same realm as sepia photographs of things long in the past.

I have also included in this show a few images from an earlier series I did about whales, inspired by the mysterious joy and strange connection I felt after eye contact with a whale mother as she put herself between her curious baby and our comparatively small boat. Working on these 45 prints and researching more deeply, I soon became haunted by the threats that loom for anything this large trying to survive on our overstressed planet. Shipping and fishing technology, deep sea oil drilling, and military sonar distort the ethereal sounds of whales calling out over hundreds of miles. These coded messages are vital to their migration, feeding and breeding patterns (and even their mental health). If you have looked into a whale’s eye, heard their singing calls, shared space with them in the sea, or seen their distant spouts in the ocean from a deserted shore, you can have no doubt that to lose these huge, wise, mysterious, peaceful beings would be a deep tragedy. Even their apparent distress and disorientation, as they search for a vanishing, once familiar world, seems to reflect our own increasing separation from the natural world. The landscape and the whales in this show belong together, and we belong with them.

I will be giving a gallery talk during the week this show is running, and will also present a printmaking demonstration at a separate time. Please check back for the times of the opening and these events.

ARTIST STATEMENT / BIOGRAPHY

Laura Clark is a painter and printmaker located in Owls Head, Maine. She studied printmaking with Nathan Oliveira in the 70s at Stanford University where she earned a BA degree in Studio Art, and a BA and MA in English Literature. She also worked briefly at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris, and at the Maidenhead School of Art in England before she moved to New York. For over 35 years she managed two careers as a college and private school teacher/administrator and as an artist, but now devotes herself full time to her visual work. She has shown for the past fifteen years in the New York area, once a year for the last ten in a two person show.

Always surrounded by animals and currently living with four dogs, her early series work includes landscape, botanical subjects, and evolving horse, dog, whale, bird and fish imagery. As a young artist she enjoyed success as a painter of unconventional portraits.

She believes strongly in interdisciplinary and collaborative processes and worked for ten years with Melinda Tepler, an illustrator, printmaker and painter. They shared a press, studio space and the same hours. Their conversations and process were integral to Clark’s work; she continues an online, synchronous, intellectual collaboration with Tepler from Maine. Clark’s second love is art history. She references artists from the past in her work, connecting with them in series she calls “Correspondences.” The first of these was with the deceased photographer Atget in monoprint interpretations of Atget’s photographs of decaying French, private estate gardens, reproducing light effects and composition in the monoprint medium. The second of these was with Ansel Adams, photographer and champion of our National Parks. The gorgeous, silvery light of Adams’ photographs appears in the more mysterious and mystical atmosphere of Clark’s monoprints. This work can be seen this July at the Granite Gallery in Tenant’s Harbor.

She has particular interest in the fate of our planet and our current tenuous connection with the natural world. Currently, in addition to the most recent monoprint series/correspondence, which is ongoing, Clark is working on watercolor collages of underwater landscapes inhabited by sea creatures and evolving human forms. She entertains visitors to her Studio in the Woods in Owls Head, Maine by appointment. You can reach her at twowhippetsart@gmail.com to schedule an appointment or purchase work. Her new website is lauraclarkstudio.com where you can see her work, and she also posts more informal images on Instagram as teatoes2. Clark also teaches individual and small group monoprint sessions by arrangement in her studio; these experiences last about four to five hours and can be arranged by email.

Description of Monoprint or Monotype

These monoprints are single images, one of a kind, painted by hand with permanent etching inks on a metal plate and preserved by laying a piece of wet 100% cotton rag paper over the image then cranking it through the heavy steel rollers of an etching press. The press utilizes hundreds of pounds of pressure to fuse the ink with the paper, creating effects of light and darkness unique to the medium. A shadow or “ghost” image remains on the plate, and often the artist will go back to the faint ink left on the plate and work back into it. This thin layer often is a beautiful, soft silvery image that gives more texture to a new image in a series.

Monoprint is different from etching and lithography in that in these mediums images are permanently etched with acid on a plate or drawn on a stone which then can produce multiple, identical images. In series, monoprints may be of one subject and related but none are identical. Both etching and lithography produce “editions” of identical prints. A finite number are made. Often, if they can afford it, artists produce a plate or stone and have an expert printer transfer image to paper, as this is a skill in itself. Artists usually not only apply ink or paint to the plate but also print monoprints themselves as this adds to the unique quality of each print.

Monoprint has been around for a long time. Initially it was a fast, sketch medium for etchers and painters. Degas used it most effectively to work through ideas he had about the figure and landscape. In early days, these images were not sold, and often were produced on scrap paper which did not preserve well. Sometimes they were produced using oil paint and rubbing on the back of the paper with hands or a spoon or using a rolling pin to transfer the paint to the paper, a technique that was less precise than the use of a press. In the mid 20th century it was still possible to purchase monoprints by noted artists for far less than their paintings, even though they were original, unique images.

Now the medium is well recognized; Nathan Oliveira and Richard Diebenkorn were two artists who famously popularized it in the 1970s. Oliveira’s technique of layering colors over each other on a single print was an important development in the use of high quality etching inks in monoprint. And Diebenkorn’s slices of pie and iconic San Francisco street depictions may be familiar to you. Many painters enjoy the technique’s flexibility and fluidity; the speed at which these images can be produced make it very effective for series work developing an idea in multiple prints